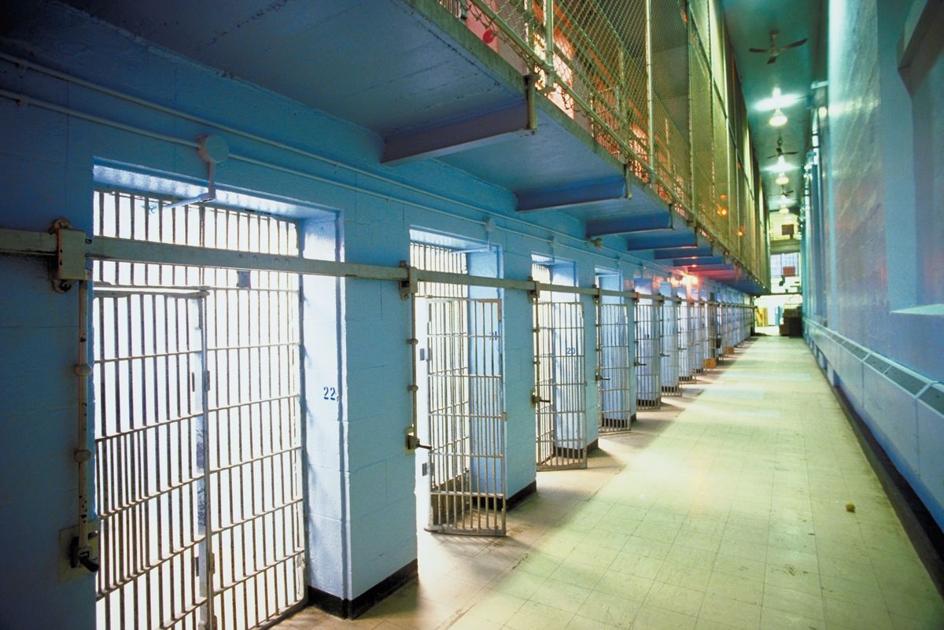

West Virginia is incarcerating more people than its regional jail system is meant to hold, and it is costing some county governments more money than they can pay.

At least 10 counties in West Virginia are more than 90 days past due on a combined $9 million in jail bills, according to the West Virginia Department of Homeland Security. That agency covers the balance with taxpayer money when payments come up short.

From 2000 to 2019, West Virginia’s jail population increased by 81% according to a report by the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy. That follows a longer national trend, Quenton King, criminal justice policy analyst for the center, wrote in the report.

“As counties look for ways to pay for needed investments in public services that could aid residents and businesses, there are few discussions about reducing the jail population despite the rising costs of incarceration,” King said.

That is paired with dwindling coal severance revenue in West Virginia, which county commissioners said they use, at least in part, to pay their jail bills.

That, officials said, leaves them to choose between allocating taxpayer money for community projects and keeping the county infrastructure functioning against covering jail bills.

“You’ve got to decide, ‘Well, do I pay for the gas we got this month, or do I pay the electric bill?’” said Webster County Commission President Dale Hall. “So, you pay the electric bill to keep your lights on, and you work with your gas vendor and say, ‘Hey, we’ll give you half this month, and we’ll try to catch up on the next month.’ ... You can’t even plan on paying anything outside of what’s keeping our lights on.”

In 2016, the West Virginia Supreme Court ordered Webster County to come up with a payment plan for what was then a $1.5 million past-due bill. By Jan. 15, the debt was $2,712,106, according to a list of counties with past-due jail bills provided by state Homeland Security.

That amount almost equals the county’s $2,744,946 annual operating budget, Hall said.

“We’ll send them what we can when we got it,” Hall said. “It’s not a whole lot. It doesn’t help diminish it because it’s growing a lot faster than what we can pay of it, but we do send what we can when we can.”

Webster isn’t alone. Lincoln, Clay, Logan and McDowell counties each owe more than $1.1 million. Calhoun and Mingo counties both owe more than $350,000. Monroe, Ritchie and Marshall counties owe more than $5,000 apiece.

County bills could be even higher

Counties are charged a daily flat rate of $48.25 per inmate, but the actual cost is more than 10% higher.

That figure is $54.88 a day, said Lawrence Messina, spokesman for state Homeland Security, which oversees the Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation that manages state jail and prison operations.

Homeland Security officials estimate the flat rate saved counties a combined $24.3 million last year.

Still, Logan County Commission President Danny Godby said, jail costs are unpredictable, causing him concern about whether the county can continue to support things like Little League baseball fields and high school athletic facilities.

“Our jail bill is probably between 15% and 18% of our budget,” Godby said. “We go out of our way to help the kids. ... That is the future, and giving them an opportunity to be competitive — they learn about being on a team. It helps them in their whole livelihood. I don’t want to get shut down to where we can’t do that.”

Logan County’s December jail bill was $123,568.25, according to Homeland Security.

As past-due bills have grown, “the state has increasingly subsidized the counties’ jail costs,” Messina said.

Counties annually are paying five figures to keep an inmate locked up who could have been bailed out for $500 or less, commissioners said. Clay County Commission President Fran King cited a case of a man caught with marijuana who could have been bailed out for $50 but wound up costing the county nearly that much for each day of eight months in jail.

Counties that fall more than 90 days past due become ineligible to receive money from the Regional Jails Partial Reimbursement Fund, which the legislature established in 2005 to offset the cost of incarceration.

“It’s a viscous cycle,” King said. “If you can’t pay it, then the state is not going to help you pay it, yet they still want us to take care of our criminal justice system and get criminals off the street. Then, we’re punished because we don’t have adequate funding to pay our jail bill.”

Clay County’s jail bill was $35,705 in December.

Fuller jails and bigger bills

In March, the state Supreme Court issued a memo to circuit judges, magistrates, prosecutors and public defenders encouraging them to seek to release more people from jail amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

By the first week of April, the state’s regional jail population was down to 4,100, fewer than the 4,265 available beds.

But the trend was short-lived, even with the state Legislature also seeking to reduce inmates’ ranks. A bill passed last year recommends magistrates release people on personal recognizance bonds, which require defendants to show up for court hearings and abide by other conditions, like taking drug tests, but do not require them to pay money.

Neither the Supreme Court nor the legislature could keep the jail population from ballooning again.

By Friday, there were 5,782 people incarcerated in the state’s regional jails, according to a Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation COVID-19 report filed with the state Department of Health and Human Resources.

Earlier this month, King said it was clear magistrates were not applying the law as the legislature intended.

West Virginia’s regional jail system houses people who are awaiting trial on state and federal charges, who either haven’t posted bond or don’t have a bond, as well as those who are serving sentences for misdemeanor and nonviolent felonies.

The state’s correctional centers house inmates who have been convicted of a crime and have been sentenced to spend time there. Counties are not responsible for the cost of incarcerating people in those facilities.

Counties are responsible for paying for incarceration on state charges until a person is either convicted or released. If a person is incarcerated solely for violating a city’s municipal code, the city pays the cost.

Following conviction, state tax money covers the total cost of incarceration.

Monitoring someone through home confinement is far cheaper. Tracking bracelets cost $5 to $12 a day, a cost covered by defendants in most counties. Ohio County frequently picks up the bill for bracelets, commission President Randy Wharton said.

“It was a lot cheaper than paying the jail bill,” Wharton said.

Cabell County has saved about $3 million a year by ramping up its home confinement program, said county Commissioner Kelli Sobonya, who served in the West Virginia House of Delegates from 2003 to 2019.

Since then, commissioners, magistrates and the Sheriff’s Office have focused on increasing the county’s home confinement efforts and paid down the jail bill. The Center on Budget and Policy Report recommends more counties dedicate resources toward putting more defendants on home confinement while they await trial so long as public safety isn’t at risk.

Cabell hired enough home confinement officers to keep track of 150 people a month, about 50 more people than the county could manage a few years ago, she said.

“Just by increasing home confinement by 50 people a month, we saved an additional $1.2 million a year,” she said. “That plays a large part in us being able to manage our bills.”

Cabell County’s jail bill in December was $188,368.

Commissioners seek changes for jail charges

Even if the state forgave all of Webster County’s jail debt, it would matter little, said Hall, the county commission president.

That’s because the county can’t cover the minimum monthly payment. December’s bill totaled $25,138.25.

“Every day that goes by, it’s that much more added on the expense,” Hall said.

Ohio County’s December bill was $68,515. The county is up to date on payments, but the system isn’t sustainable, Wharton said.

“There should be, maybe, some reallocation back to the counties,” Wharton said.

Sobonya and other county commissioners said legislative efforts have come up short in getting municipal and state police to use some of their budget money to help cover the cost of incarcerating the people they arrest.

Because the state largely operates jails, Sobonya said, counties are limited in their ability to offer input or otherwise limit costs, but she is ready to have the discussion with lawmakers.

“Our hands are shackled at the county level,” Sobonya said. “We don’t have control of our destiny.”

Logan County’s struggles have been exacerbated by coal’s decline. Coal severance revenue has fallen from $900,00 to $1 million to about $300,000 a quarter. County Administrator Rocky Adkins said there needs to be a comprehensive effort to decrease the jail bills.

He suggested in addition to forgiving the jail debt, the legislature consider placing a cap on how much money counties are responsible for paying to incarcerate people. He also urged attention to providing more resources to county prosecutors, public defenders, circuit courts and magistrate courts to help cases move faster through the court system. He called for a funding formula for jail costs.

“We have got to have a long-term fix, not a temporary fix,” Adkins said. “We can’t just keep sitting in a desolate area and expect to move forward in West Virginia. ... We are a county that pays our bills. This is getting ridiculous.”

"pay" - Google News

January 31, 2021 at 05:00AM

https://ift.tt/3oFsCOA

Crowded jails costing counties more than they can pay - Charleston Gazette-Mail

"pay" - Google News

https://ift.tt/301s6zB

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Crowded jails costing counties more than they can pay - Charleston Gazette-Mail"

Post a Comment